First Published: 1964

1st published by:- Michael Joseph Ltd, London, 1964

QUALITY BOOK CLUB EDITION : 1964 (pictured)

Reprinted (Kinship Library) Paperback, 1992

QUALITY BOOK CLUB EDITION : 1983

Hardcover 324 pages with dustjacket

Publisher: The Quality Book Club, London

ISBN: N/A

Size 20.5cm x 13.5cm x 2.8cm approx

weight 380g approx.

Book Description:

"This is the story of how the British race was persuaded, shamed and legislated into showing mercy to the "brute creation". It traces the course of controversies over stag and fox hunting, the art of "shooting flying", cock-fighting, the pursuit of big game, vivisection, the bearing rein, performing animals, the spreading of myxomatosis, the introduction of broiler-houses and many other practices which have raised passions. Apart from its controversial issues, this book opens up an unusually rich seam in social history, piquantly presented."

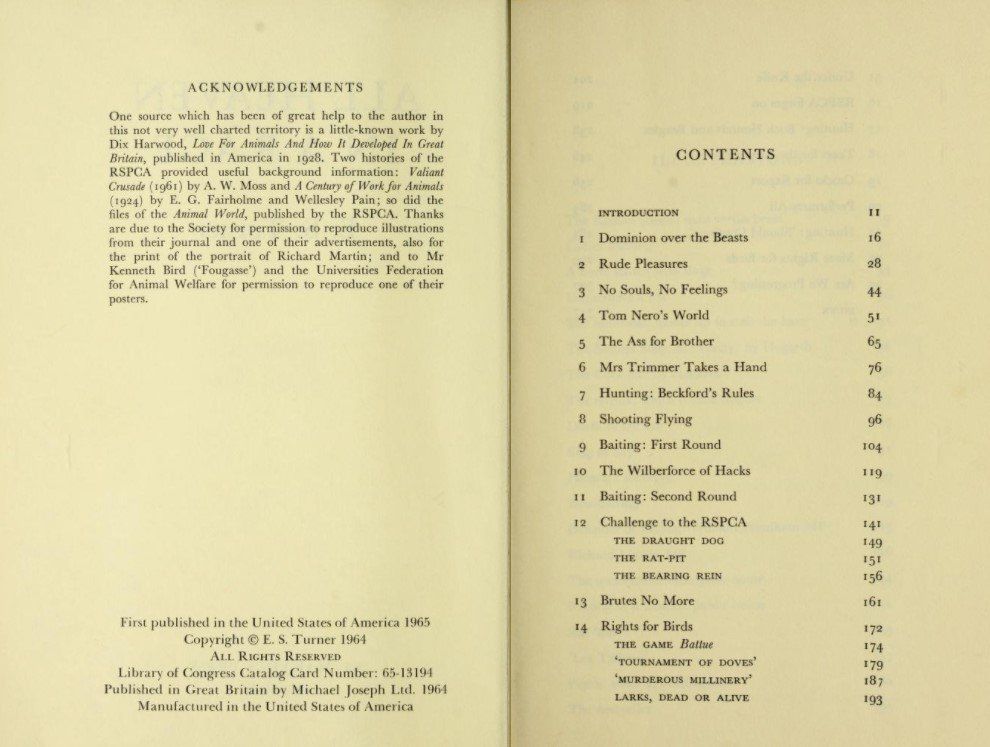

Acknowledgements:

One source which has been of great help to the author in this not very well charted territory is a little-known work by Dix Harwood, Love For Animals And How It Developed In Great Britain, published in America in 1928. Two histories of the RSPCA provided useful background information: Valiant Crusade (1961) by A. W. Moss and A Century of Work for Animals 1924) by E. G. Fairholme and Wellesley Pain; so did the files of the Animal World, published by the RSPCA. Thanks are due to the Society for permission to reproduce illustrations from their journal and one of their advertisements, also for the print of the portrait of Richard Martin; and to Mr Kenneth Bird ('Fougasse') and the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare for permission to reproduce one of their posters.

CONTENTS:

INTRODUCTION

1 Dominion over the Beasts

2 Rude Pleasures

3 No Souls, No Feelings

4 Tom Nero's World

5 The Ass for Brother

6 Mrs Trimmer Takes a Hand

7 Hunting: Beckford's Rules

8 Shooting Flying

9 Baiting: First Round

10 The Wilberforce of Hacks

11 Baiting: Second Round

12 Challenge to the RSPCA

THE DRAUGHT DOG

THE RAT-PIT

THE BEARING REIN

13 Brutes No More

14 Rights for Birds

THE GAME Battue

'TOURNAMENT OF DOVES'

'MURDEROUS MILLINERY'

LARKS, DEAD OR ALIVE

15 Under the Knife

16 RSPCA forges on

17 Hunting: Buck Hounds And Beagles

18 Tears for the Elephant

19 Crocks for Export

20 Performers All

21 Hunting: 'Should Continue'

22 More Rights for Birds

23 Are We Progressing

Illustrations:

The Roman venatio: man versus beast

Ladies hunting

A horse baited with dogs

Unearthing a fox

The huntsman moves up to stab the hart

The Second Stage of Cruelty: by Hogarth

The Cock-pit: by Hogarth

The sermon which roused disgust

Death of the fox

Stag at bay

Pheasant shooting

Bear-baiting

Defender of Baiting: William Windham

MP Richard Martin MP

The underground slaughter-house

Ratting in a London public-house

Rat 'hunt'

'Lex Talionis'

Pigeon shoot at Hurlingham

The nest seller

The bird catchers

The dog manglers: by John Leech

Water for man and beast

A Victorian hero: Greyfriars Bobby

The Prince of Wales slays an elephant

Van Amburgh and his lions

'Unnatural Elephantics'

Was This the Trap?

Introduction:

THIS book sets out to describe how the British nation was persuaded, shamed, shocked and coerced into showing mercy to the 'brute creation'. It deals with the social, philosophical and legislative aspects of that struggle. :'or reasons chiefly of space it is concerned with the cruelties of peace, not of war. Much in these pages is capable of rousing passion and controversy, but the writer would like to think he has achieved a certain restraint in the telling.

The germ which led to this book was picked up long ago in a Chicago slaughter-house. A sign over a corridor read:

THIS WAY

TO SEE

THE KILLING

As the corridor changed direction the sign was repeated. Then a new notice appeared:

THOSE WHO DO NOT

WISH TO SEE THE

KILLING, STOP HERE

Nobody stopped there. Who could endure the shame of halting under a notice like that? Next moment all were spectators of semi-mechanised hog-spearing: a brutal sight, a brutal noise and a brutal smell. Then came the primitive pole-axeing of steers. Afterwards, in a canteen, all the sightseers ate strips of cooked bacon and filled in a questionnaire saying which they preferred.

It was not like going to a bull-fight, one of the party argued, defensively. Slaughter for food was necessary, slaughter for art was not; people ought to know what was done to animals on their behalf. He may have been right. But the spirit in which most of the party went through the slaughter-house was that in which so many tourists go to the bull-fight: to see whether they would be sick or not.

The British would quickly find moral objections if slaughterhouses in their own land were thrown open to tourists, just as they would object to the introduction of bull-fighting. Their opposition would be based on fear of how such spectacles might degrade their fellow human beings. How such apprehensions have influenced the campaign against cruelty these pages will show.

In our attitudes to animals we are hopelessly, perversely inconsistent. There have been fox-hunters who revolted at the idea of performing animals. Game shots who litter the ground with cripples denounce deer-hunters as barbarians. Old ladies assault men who try to kill pigeons, but keep cats which destroy birds. Women wearing 'cruel furs' used to criticise women who wore 'cruel feathers'. People send cheques to the RSPCA and next day eat pate de Joie gras, which the Society begs them not to do. All of us applaud the trouble taken to tranquillise and lift hippos from the sites of dams, but none of us care whether rats are killed humanely or cruelly. Nobody has ever started a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Fish. The law is riddled with illogicality. A dogs' home is awarded damages against an author who said that its dogs were sent for scientific experiments; yet experimentation is not only legal but, in some contexts, compulsory. In a sentimental moment the law exempted stray dogs from being sent to the laboratory, while leaving householders free to sell their unwanted pets for this purpose. A clergyman has to pay damages for saying that a fox was dug out and thrown live to the hounds, but if the hounds catch a live fox and kill it, well, that is the purpose of hunting.

If there is much about hunting and shooting in these pages, it is because this is the ground on which people are always spoiling for a fight. The rules of sportsmanship ought to be taken out and re-examined by every generation. In 1951 the Committee on Cruelty to Wild Animals, which found in favour of almost all field sports, said that future generations might well regard the cult of sportsmanship, with its basic lack of logic, as 'an outmoded virtue, tainted by its origin'. A hundred years earlier the Quarterly Review, after brooding over the ethics of playing a salmon, summed up thus: 'In no sport is the mere

extinction of the animal's life the principal object - the very word implies the reverse; it implies time for pursuit, that is, time for mortal fear, time for anguish. In the exact proportion that you abridge your pastime you bring yourself nearer to your butcher; and abridge the process as you may, you never can be so humane, in your actual character of executioner, as the tradesman in the blue apron may be - and as the law should compel him to be in all cases whatever.* Sport has been described as the observing of rules to make difficult -bat would otherwise be too easy - or should it read 'what would otherwise be too humane'? Up to a point the law upholds the sporting principle. If coursed hares have inadequate facilities for escape, the promoters of the event may be prosecuted. But the law does not mind how many foxes' earths are stopped up. The sporting Englishman refuses to worry over-much about these things. 'This amiable man,' note Miss Victoria Sackville-West, 'to whom organised cruelty would be abhorrent should he once recognise it as such is enabled by his peculiar national and racial capacity for the avoidance of lucid thinking to esteem himself rather a fine fellow under cover of that good totem name of sportsman.

In shooting, which causes far more suffering than hunting but attracts less indignations, the code of sportsmanship involves the man with the gun in idiotic dilemmas like that posed by the writer in Shooting Times (December 27, 1963). Faced with a very high-flying pheasant he said to himself: 'If this were a duck, it would be bad manners to fire at a bird palpably out of shot . . . as it is a pheasant I suppose it would be bad form not to fire' (he fired and missed). The general standard of marksmanship in a land where anyone can buy and use a shotgun can never be high. Thousands of 'sportsmen' observe no rules whatever; in 1962 more than half the deer killed in the Forestry Commission's woodlands had gunshot wounds in them. Shooting is encouraged by a powerful industry and every effort is made to bring up new generations in the tradition. Another writer in Shooting Times (November 30, 1962), describing Christmas shoots for boys, said: 'Now and again a boy would "connect", to his own and everybody else's surprise, and you would see on his face the bliss that passes all understanding . . .' In the same issue a pundit said: 'Respect your quarry and do not think of it, or treat it, as some lowly form of animal life.' The hallmark of a sportsman is that he can do this and yet feel, if he does not always show, the bliss that passes all understanding when he 'connects'.

The basic question, in hunting and shooting, is: 'Should killing for amusement be left to the individual conscience?' Or is it one of those forms of self-expression, like rape and the seduction of minors, which call for legislative restraint? Long ago the law decided that baiting should not be left to the individual conscience. Under one Socialist Government an attempt to suppress hunting failed, the time being regarded as unpropitious. Next time a similar Bill might squeeze through. But it is difficult to imagine Parliament passing an Act to limit shooting.

Nowadays the animal 'crank' - the person who used to ask, when shopping, 'Was it humanely killed?' or 'Was it humanely trapped?' - finds it harder to make a personal stand against practices he detests. Before the last war it was possible to order coal from non-pony pits, thus causing a certain disorder in the coal trade; but zoning of supplies ended all that. The electricity we switch on may owe its existence to pit ponies. The anti-vivisectionist knows by now, or ought to, that hundreds of medicines are tested on animals - are they all to be rejected? Fats and cosmetics may come from whales killed by explosive harpoons (blow a hole in a man, anchor a rope in his wound and make him pull a loaded barrow for an hour or two- that is a rough comparison). Not many of us care about whales; they are majestic and mysterious, but readily overlooked. It is easier to boycott a circus than to boycott soap. It is easier still to live and ask no questions.

People have wondered whether the RSPCA came into being because Britain was exceptionally kind to animals or because some such body was exceptionally necessary. The answer, surely, is that it was formed when the British conscience was more sensitive than those of other nations. 'The greatness of a nation consists not so much in the number of its people or the extent of its territory as in the extent and justice of its compassion,' says the inscription on the memorial at Port Elizabeth to the horses lost in the South African War. A statement of this kind would have been a blazing irony if a similar monument had been erected in Britain overlooking one of those ports from which cavalcades of broken-down horses were shipped by 'sausage boat' to the Belgian abattoirs - in times of peace. But when all the ironies and anomalies and hypocrisies have been discounted, Britain can still claim a wider range for her compassion than most countries. In two lands which claim to be the founts of Liberty things are done to laboratory animals which are not tolerated here. And Britain at least has abolished the gin trap, while most of the

world retains it (she still imports the products of other nations' gin traps).

Her next step, perhaps, is to temper the harshness of the industrial revolutions on her farms.